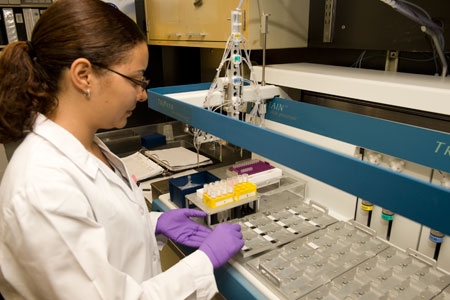

Cytopreparatory laboratory technician processing a liquid based gyn specimen

In the United States, the death rate from cervical cancer has declined dramatically in the last half century. This can be directly attributed to the earlier diagnosis of precancerous lesions (intraepithelial lesions) by the Pap smear. This simple test is the most effective cancer screening test in medical history. It has been responsible for the 70% to 80% decline in deaths due to cervical cancer over the past decades.

BOTTOM: Conventional Pap “smear” with hills and valleys of specimen

TOP: Completed Pap specimen using the liquid based methodology

Cytopathology, the discipline of microscopical analysis of human cells for the purpose of discovering the presence of disease, is the division of Pathology that receives Pap specimens from our hospital clinics and inpatients, as well as our affiliate sites around Maryland. In the 1940s George Papanicolaou, a Greek physician and physiologist, studied the human menstrual cycle. During his work he noticed highly atypical cells coming from the cervix of some of his patients who were ultimately diagnosed with cervical cancer. After the “Pap” smear was born, and for the next 40 years, gynecologists sampled their patients’ cervices with wooden or plastic spatulas and brushes and smeared the cells obtained onto microscope slides. After the slides were accessioned and stained, a cytotechnologist would examine each specimen for the presence or absence of cancer or one of its precursor lesions. Mind you, there might be 200,000 cells (epithelial, inflammatory, blood) on a slide one inch by three inches! There had to be an easier way!

Cytotechnologist examining a liquid based Pap

It turned out there was an easier way. In the 1990s the first liquid-based gynecologic preparation method was FDA approved, and another, similar, method followed shortly thereafter. Instead of smearing a heterogeneous population of cells onto a slide, creating valleys and mountains of specimen, the new technique allowed the specimen to be collected into a liquid-based medium. This vial, once received in the lab, was homogenized and only a small part of the sample was used to make the “Pap.” Now, it couldn’t be called a Pap smear, because the material was deposited in either a 13mm or 20mm circle on the slide. The Pap “smear” had evolved into a “liquid-based” Pap specimen. Cytotechnologists were now able to microscopically examine 20,000 cells with more efficiency, confidence and greater sensitivity than in the past. The clarity of the new methodology removed some of the doubts that the cytopathologists (the physicians) had regarding “funny-looking” cells that were called “atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance.” Unfortunately, it didn’t answer all of the questions. Were these atypical cells just unusual normal cells? Did they represent a reactive change to an infectious agent? Were they just a few cells from a significant intraepithelial lesion? There had to be something else that could be done with the extra specimen in the vial to resolve these remaining questions.

Cytopathologists conferring on a case

Some of these questions have been addressed by testing Pap specimens for the presence of human papillomaviruses (HPV). Infections with HPV are common and there are more than 100 different types of HPV. Many HPV types are harmless. Others cause warts on the skin or genitals and some types (so called “high risk HPV” types) can cause cancer of the cervix, vulva, vagina, and anus in women or cancers of the anus and penis in men. Tests for high risk HPV types detect virus genetic material that is present in Pap specimens. These assays have become widely accepted as the next testing step for Pap smears that show atypical squamous cells. Women whose Pap smears have atypical squamous cells but no detectable high risk HPV have a very low risk of an underlying pre-cancer or cancer. No further testing is recommended for these women other than their regular annual Pap. Women found to have atypical squamous cells and high risk HPV should undergo further examination of their cervix to identify a potential underlying pre-cancer or cancer. It is important to note that the presence of high risk HPV does not mean that cancer or a pre-cancer are present.

Medical technologist processing the specimens for HPV testing

Recent studies have shown that high risk HPV tests of cervical specimens can be used in combination with Pap tests to identify women who can safely have Pap testing at intervals greater than every year without increasing their risk of cervical cancer. These studies showed that women older than 30 years of age with a normal Pap test and no evidence of high risk HPV in their cervical specimen had a very low risk of cervical cancer over the next 5 years. Based on these results, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control have recommended that women should have an annual Pap test until the age of 30. Women older than 30 years of age can be screened with Pap and high risk HPV tests. If the Pap test is normal and no high risk HPV is detected, women can be screened again in 3 years.

Cervical cancer can now be prevented by methods in addition to cervical screening. In June 2006, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a vaccine (trade name “Gardasil”) for the prevention of infection by the two HPV types that cause most cervical cancers (types 16 and 18) and the two types that cause most genital wart (types 6 and 11). The vaccine is given in three doses over a period of six months. It is most effective if given before a woman becomes sexually active.

Fran Burroughs, SCT (ASCP) IAC

Cytology Supervisor of Technical Operations

Ame’ Maters

Manager, Microbiology and Immunology Laboratories